If we can look around our house, we can see that there are many items or appliances (especially kitchen appliances or electronic appliances) that are not new, and are age old. Few such examples are our mixer, grinder, refrigerator, washing machine, etc., which have been with us for a long period of time. Maybe 25 to 30 years old. This is even clearly evident with our parents or the previous generation people, who try to keep these appliances for many many years. For instance, my mom uses the refrigerator that she had bought it some 25 years ago. The mixer she has is also clearly more than 25 years old. Even if we do not get the spare for these appliances, they try to get it somehow, but do not replace it with a new appliance, even if we can afford to get it now.

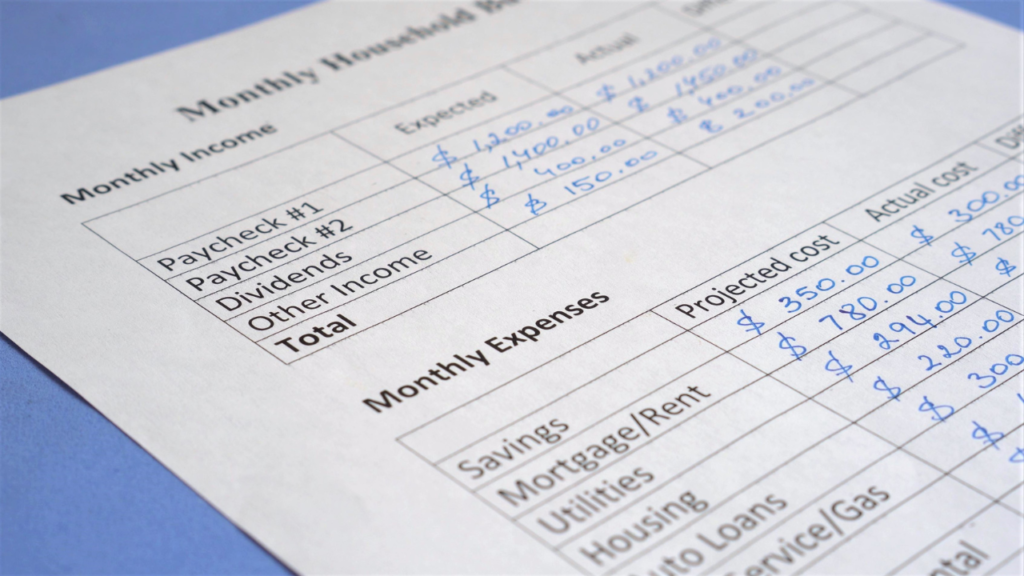

Why is my mom unwilling to see that the market for kitchen appliances has long gotten so advanced, that she can replace her appliances with something new? But the argument from my mom is that “it is still working, so why should I change it?” In personal finance terms, we can look at this item as capital expenditure and not revenue expense. The appliances were in those days considered as Capital expenditure by our households (A capital expenditure is large, not incurred routinely, and spent on an item intended to be used over several years). These were not considered as a revenue expense in those days (Revenue expenditures are short-term expenses used for items that last typically one year or so. Revenue expenditures for a household include the expenses required to meet the on-going costs of running a family).

A capital asset would be depreciated by a company in order to expense a piece of it each year. A home would not do it the same way since it does not operate for profit. However, maximization of wealth is a financial goal for households. Money saved rather than spent adds to this goal. So, it makes sense to be frugal with your money.

I have in this article discussed about this shift in mind-set between capital and revenue expense that has happened across households (especially that has happened between the previous generation and the current generation). It might not be a cause for concern for the current generation, but for the enthusiastic nostalgic people, this is still not an easy shift in mind-set though.

There was a time, say 30 years ago, when my mom bought her refrigerator or mixer-grinder, when household incomes were insufficient. A middle-class family had a tense final few days of the month while they awaited their next salary. Any major expenditure necessitated some compromise and patience. Banks did not make retail or personal loans so easy back then. Employees obtained advances from their employers or purchased products from businesses that provided instalment payment plans. It made sense to be thrifty with every cost at the time. And capital costs were to be spread out over as many years as possible to keep the financial load as low as feasible.

Penalizing frugality and getting settled for concessions in quality, efficiency, and speed were part of the older generation’s mind-set, and they assumed that these things had to be done as part of one’s financial life. The prior generation may be trapped in this story.

However, times have changed. It is currently fairly usual for middle-class families to have a sufficient amount in their savings bank account before the pay day. A big portion of the population’s income has risen. Capital expenditures are not difficult to incur because loans are readily accessible to purchase anything that does not fit into a typical monthly salary. Repayment via EMIs is seen as a simple approach for eliminating huge capital expenses.

Current generation households are unconcerned about the loan calculations or the effective rates of interest, as long as the EMI is easily accommodated within the monthly income and allows a sufficient cushion for other costs and savings. Banks and Financial institutions are now enthusiastic lenders to the retail market, who are eager for business and attempting to maximize the amount of EMI a given income can endure.

Capital asset markets have also evolved considerably. The most crucial is the property market, which is likely the most desired capital asset for a family in the middle class. A home represents a real capital spending choice for a family. But the only point that we need to ponder in for this capital asset (which is the house) is the residual value of this capital asset after paying off the home loan, and the years over which that would be leveraged.

But practically everything else is no longer a capital expense. Many consumer items have become less expensive as a result of plentiful availability and improved technology and efficacy. Because of rising salary, the cost as a proportion of median family income has decreased. As a result, anything from cars to mobile phones, vacations to home appliances, clothing to dining out is a household’s usual revenue spend nowadays.

If a car loan is repaid off in three years, the borrower is more likely to take out a new loan to make the switch to another new car. This is because the borrower views the EMI as an expense rather than a capital outlay. The real and intangible advantages associated with driving a newer car, as well as the capacity and desire to spend that amount, have drastically altered how customers behave. It may not be profitable to battle with an outdated car or to be proud of your thriftiness.

This shift in mind-set benefits a whole system of manufacturers, lenders, service providers, and tax-collecting authorities. We could be tempted to label this propensity as consumerism and start listing the flaws. We might also profit from observing the socio-economic inclinations that emerge as a result of abundance and success. Because of this shift of perspective, the world may be a better place. It would be much better if we could additionally solve for waste, garbage, recycling, and other societal expenses associated with this conduct of consumerism.

As a society, we may be transitioning towards a generous mind-set that feels there is sufficient for everyone. We may be comfortable in our ability to obtain work, generate a sufficient income, spend it to make our daily lives more pleasant, and be courageous in examining alternative uses for our money. This story may be appealing to a younger audience.

Both segments may have gone overboard in their pursuit of their preferred story. The young may think the old are excessively frugal and unduly tight-fisted, while the old may think the young are irresponsible in their spending and forget their financial goals. But it’s impossible to say where the middle point is since we see supporting reasons for both narratives. These are just various hypotheses about how much money is required, how long it will last, how much must be saved and how much should be spent judiciously. We don’t know the answers to any of those questions. We’re not going to search for the answers either. We will just go with the trend, but the newer generation need to be cautious as well, as the household debt as percentage of GDP has risen to 40% of GDP, from 30% of GDP some 10 years ago. Also, household debt as a share of personal disposable income has risen by about 20 percentage points since 2012. So, the newer generation begets caution here when it comes to consumerism.

Frugality is a virtue.