Often considered the founder of value investing, Benjamin Graham developed a defensive investment approach that attempted to save investors from large losses while yielding modest gains. His approach to investing focused on choosing undervalued, financially stable businesses with a “margin of safety.”

Graham offered a rigorous framework for assessing defensive investing strategies in his well-known book Security Analysis, placing a strong emphasis on careful consideration and good judgment. He listed the two main strategies for defensive investors:

- In order to reflect the market as a whole, he advised investment in a diverse portfolio of reputable, reliable businesses. By using this strategy—often called passive investing—investors were able to lower the risks involved in picking individual stocks.

- Graham then recommended building a portfolio of individual stocks using both analytical and subjective standards. It was advocated that defensive investors give preference to long-established companies with solid financials, less debt, and a track record of consistent profits. To offer diversification and lessen exposure to market fluctuations, this approach balanced high-quality bonds and equities.

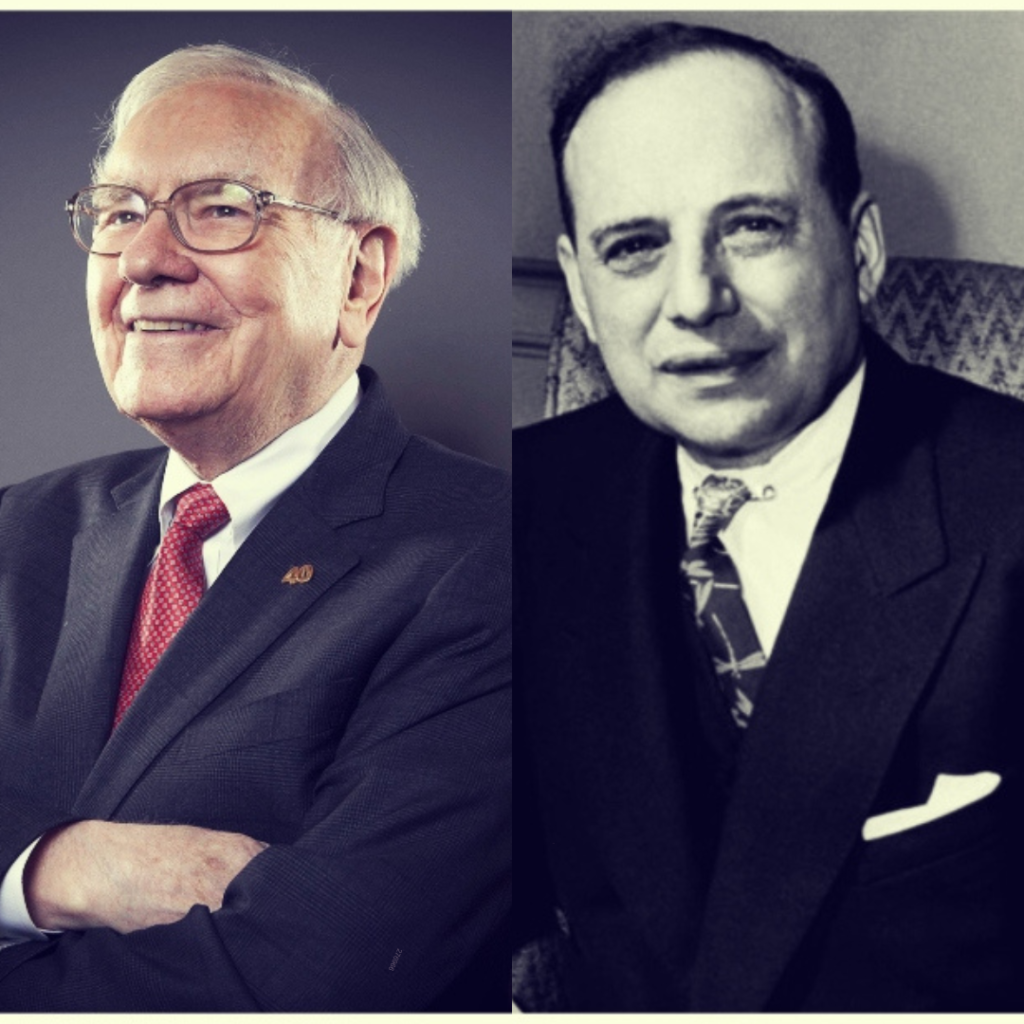

Although the majority of Graham’s lessons are still applicable today, his most famous and favoured student, Warren Buffett, has modified them to suit the times. Buffett’s adjustments provide an intriguing viewpoint on changing investment methods for individuals who adhere to Graham’s ideas.

In this blog-post, we will look into the various concepts that Warren Buffett has adopted from Graham’s framework, but with some changes to these concepts that suit the modern context of businesses.

Does Size of the company matters?

Investing in businesses of the right size was one of the main tenets of Graham’s approach. Graham aimed to reduce the chance of severe volatility or failure by focusing on big, well-established companies with a lot of resources and capabilities. These businesses were more resilient to market upheavals and economic downturns because they frequently had a strong financial foundation and a position of strength in the market. The reasoning was simple: bigger businesses are more likely to be stable because they are more diverse and have easier chances of getting financing, which lowers the risk of insolvency.

But one of Graham’s most well-known students, Warren Buffett, changed this approach to fit his own investing philosophies. Buffett expanded on Graham’s focus on big enterprises by highlighting superior companies with strong edge over their competitors, or have “economic moats.” The term “economic moat” refers to a company’s competitive advantage that secures its market position over time. Companies having a broad economic moat make it harder for competitors to invade their market share. Warren Buffett made this phrase popular.

Buffett realized that not all big businesses are fantastic—some have more robust operating models, more recognizable brands, or technological strengths that distinguish them from their competitors.

Buffett’s investments in companies like Apple, Coca-Cola, and American Express are prime examples of his concentration on businesses with significant advantages in the marketplace. These businesses are able to sustain their market position and provide steady cash flows due to their distinct competitive advantages in addition to their significant market footprint.

Liquid and less Levered:

Another crucial component of Graham’s defensive approach was his emphasis on liquidity and financial stability. He advised investing in businesses that had a high current ratio—ideally at least 2:1, which indicates that the company’s current assets exceeded its current liabilities by a factor of two. This ratio reduced the likelihood of financial difficulty by showing that the business could easily meet its short-term commitments.

Although Warren Buffett prioritizes long-term debt, he shares Graham’s conservative attitude to the stability of finances. By calculating how long it would take to pay off all debts with current profits, Buffett emphasizes how well a business can manage its debt over time.

According to Buffett, having too much long-term debt can be risky, especially when the economy is struggling and revenues could drop. Businesses that have acceptable debt levels are better equipped to withstand difficult times and ensure their long-term viability.

A key component of Buffett’s approach is his emphasis on long-term financial stability. He steers clear of businesses that rely significantly on borrowing to finance operations or have excessive levels of leverage. In order to preserve financial versatility and steer clear of high risk, he favours companies that have adequate cash flow to easily cover their debt.

Viewpoint on Dividends differ:

The most important aspect of Graham’s defensive investing approach was dividends. Companies having a lengthy history of reliably paying dividends, in his opinion, showed both financial stability and a dedication to giving shareholders their money back. Graham advised investors to give consideration to businesses that had paid dividends consistently for at least 20 years.

In contrast, Buffett views dividends differently. His company No dividends have ever been paid by Berkshire Hathaway under his chairmanship. To support long-term growth, Buffett would rather put earnings back into the business. According to him, keeping profits in-house can eventually increase returns for shareholders, particularly if those funds are put toward company growth, acquisitions, or investments in fresh prospects for development.

Buffett also highlights the tax drawbacks of dividends, pointing out that dividend income are subject to regular slab rates, but long-term capital gains on the sale of shares are subject to reduced rates. Because of this, long-term investors find capital appreciation more alluring than dividend income. Buffett’s position on dividends is consistent with his larger investing thought process, which prioritizes long-term value building above immediate profits.

Stable earnings:

Graham’s focus on income stability was another important component of his approach. He considered that only businesses having a track record of profitable operations over the previous ten years should be taken into consideration by investors. By ensuring that the business showed steadiness and durability over a considerable amount of time, this measure reduced the likelihood that it would experience unexpected financial difficulties.

Over time, this emphasis on long-term profit stability made investments in businesses with erratic or unexpected revenues less risky and more dependable.

Buffett is more flexible in his strategy even though he values earnings consistency. Instead of demanding a rigorous ten-year history of positive results, he places an emphasis on steady earnings increase over time. Buffett believes that a business’s capacity for long-term growth—even in the face of random setbacks—is more significant. If he thinks the business has considerable growth potential and is solid in its foundation, he is prepared to forgo a year or two of negative earnings.

This kind of more adaptable strategy enables Buffett to seize chances in businesses that could be momentarily undervalued as a result of transient problems. Buffett seeks for businesses that are poised to expand in the future, even if they have faced recent difficulties, rather than rigidly following historical profits.

Stock valuation:

Benjamin Graham used the price-to-book value (P/B) ratio to determine the intrinsic worth of stocks. According to him, the stock price of a company shouldn’t be more than 1.5 times its book value. This cautious strategy gave investors a margin of safety by ensuring that they were purchasing stocks that were being sold at or below their actual worth.

Warren Buffett, on the other hand, prioritizes a company’s intangible attributes over its P/B ratio. Buffett is aware that intangible assets like client trust, proprietary information, and brand power account for a sizable amount of the value of many prosperous businesses. These intangible assets can be important sources of long-term profitability and competitive advantage, even if they might not be completely represented in a company’s book value.

According to Buffett, these intangible assets support the company’s profitable growth and economic success, which justifies a higher P/B ratio.

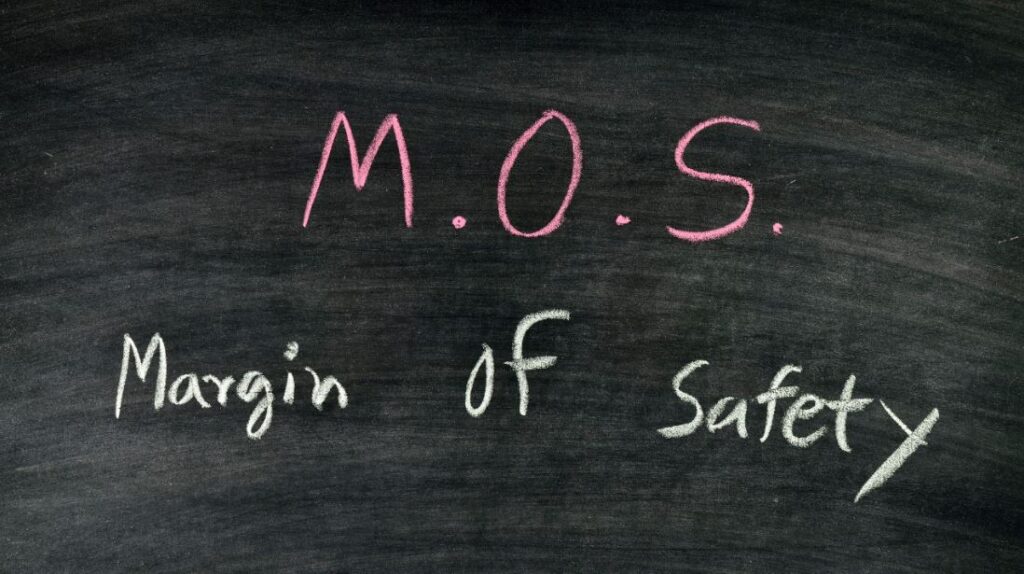

The key aspect – “Margin of Safety”:

Developed by Benjamin Graham, the “margin of safety” is one of the most widely recognized value investing concepts. To guard against possible losses, it entails purchasing securities at a large discount to their true value. Investors protect themselves against unanticipated stock price drops by investing less than what the company is worth.

This idea has been modified by Warren Buffett to fit the needs of the modern marketplace. Buffett is more concerned with the quality of the company and its potential future prospects, even if he still appreciates the margin of safety. Buffett believes that investing in high-quality companies at fair prices is what constitutes the margin of safety, not simply purchasing inexpensive stocks or using an intrinsic value number as a benchmark.

Buffett’s wider investment philosophies are reflected in his application of the ‘margin of safety’ idea. He thinks that businesses with significant competitive advantages offer a margin of safety in and of itself, thus he is prepared to pay more for them.

Growth in earnings of companies:

Graham used a quite simple strategy to earnings growth. He demanded that businesses should increase their earnings per share by at least one-third (33.3%) during the previous 10 years. By ensuring that businesses were expanding faster than inflation, this criterion made them desirable long-term investments.

Buffett takes a more proficient method for measuring earnings growth. Although he favors businesses with significant room for expansion, his standards are not as strict as Graham’s. Buffett admits that certain businesses may go through times of sluggish growth or brief setbacks, particularly those in cyclical sectors.

Buffett’s emphasis on profit growth is less about hitting certain short-term goals and more on the company’s long-term trajectory. If he thinks the business has a chance to succeed in the long run, he is prepared to ignore short-term profit dips.

Diversification approach:

Diversification as a risk-reduction tactic was something Graham strongly supported. He thought that investors may lower the risk of any one stock underperforming by distributing their money over a variety of sectors and asset classes.

Buffett, on the other hand, approaches diversity differently. He would rather focus his investments on a select group of superior businesses that he is well-versed in. According to Buffett, diversity results from knowing the companies one invests in. Buffett claims that it is preferable to possess a small number of businesses that are strategically placed for long-term growth rather than a huge number of equity investments.

Buffett believes that in-depth understanding of the companies he invests in, rather than diversification, is an essential component to lower investment risk.

Final words:

Who are the actual value investors, then? Is it Ben Graham and other investors that prioritize low PE and P/B stocks, or is it Warren Buffett and similar investors? It turns out that both groups are value investors.

Value investing has changed over time—not because the game’s rules have changed or anything—but primarily because of changes in the modern market, investment capital’s size, and demographics of the stock market.

Buffett has shifted to the modern thinking because his assets under management have increased dramatically, not because the rules of value investing have changed. These days, he purchases larger businesses with P/E and P/B multiples that are greater than usual. However, due to their substantial and long-lasting competitive advantages, these businesses continue to be value stocks.