Millions of Indians fight an arduous battle every day, Monday through Friday. Starting at 9.15 AM, the battle lasts until 3.30 PM, and then it starts over the next day! What precisely is the war over, though? It ultimately comes down to determining a stock’s fair value, which is arguably the most perplexing of all conflicts.

As fundamental investors compete, other competing forces such as technical investment, momentum investing, or passive investing have a considerable impact on the course of events, generating further ‘distortions’ in price vs value. In addition to the major wars that the great players engage in, there are smaller conflicts that little traders and investors like us participate in. Therefore, how can stock markets exist if all sellers believe they are getting a fair exit price and buyers believe they are getting a good entry price?

As they say, no two doctors, no two lawyers, and no two astrologers agree; similarly, “no two investors/analysts agree”.

Every fundamental investor tries to master the art of valuation, but very few are successful. Those that are successful in it become extremely wealthy.

First things first – Let us see ‘What is Valuation’:

There has never been a more sharp disparity between what is defined and what is understood. Market gurus like Warren Buffett and Aswath Damodaran define a stock’s worth as the net present value of all potential future cash flows. This definition is straightforward. To put it another way, this is the “intrinsic value” of a stock that Warren Buffett values most. Buffett notes that “this intrinsic value is a number that is tough to identify precisely, but vital to estimate” at the same time. As a result, determining a stock’s worth is rarely as straightforward as defining it.

So, the question comes that – Why do we need to engage in such Complex task?

We have already discussed this instance in one of my other post some time ago, but I thought it would be useful to requote that again in this blog-post as well.

Renowned hedge fund manager Bill Ackman’s company, Pershing Square, was ranked among the top 20 worldwide hedge funds in January 2015 after achieving $4.5 billion in net profits in 2014. This accounted for 40% of the company’s total gains over the ten years prior to 2014. Bill Ackman was the youngest person in the elite league, serving for the company for 11 years and being 48 years old.

But a little more than a year later, everything was reversed. Bill Ackman lost more than $3 billion on just one bet alone when his huge gamble on Valeant Pharmaceuticals went horribly wrong. Market-listed Pershing Square Holdings saw a more than 50% decline between early 2015 and early 2016. Many years of prosperity were destroyed by a single wrong bet, and it took around four years to recover from the losses.

Bill Ackman regretted that this was the single instance in which he violated all of his investing principles in an insightful interview following his exit from Valeant Pharma bet at a 90% loss. Pershing Square’s usual approach was to purchase concentrated positions in high-quality businesses that were undervalued (in relation to intrinsic value) and whose business they could analyse and comprehend by simply reading their 10Ks (which are comparable to annual reports) and making reasonably accurate predictions about future cash flows.

However, in Valeant’s instance, they departed from their investment principles by first collaborating with the company and then investing in it without using their customary research/valuation-based method since they felt comfortable with the management.

We can take away from this episode that a methodical, rule-based approach to valuing is important. Aswath Damodaran, the ‘Dean of Valuation,’ describes valuation as a life jacket he may cling to in turbulent times. Given the prejudices that people are prone to, he asserts that investors will always find a reason to purchase or sell a company. Valuation “allows your logical side to present an argument and slows down the process.”

Even one of the greatest investors in the world, Bill Ackman, realized that a single error resulting from a biased choice might reverse years of profits. What about the others, if the greatest of breed can make such mistakes?

Therefore, when it comes to investment valuation, we must adopt a process-driven strategy. Your attitude to valuation may discourage you from purchasing the popular stocks that are causing a stir in the market. And, in rare occasions, one of the frenetic hot stocks may even become a true multi-bagger, as Tesla did, but it would also have spared you from losing 90 to 100 percent of your money by preventing you from investing in numerous other companies that plummeted. Errors of omission are preferable than errors of action in the realm of investment. That is how Warren Buffett rose to become one of the world’s wealthiest individuals.

So now that we know why valuation is important, how should you go about it?

Valuation is an art:

Largely there are two main approaches – Absolute and Relative valuation.

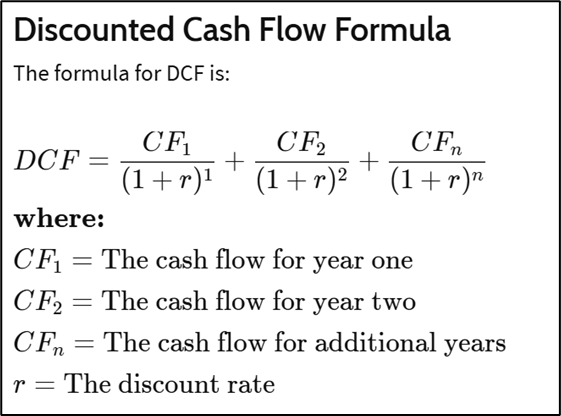

The absolute method entails figuring out a company’s intrinsic value. Two popular methods are used here as well: the dividend discount model, or DDM, and the discounted cash flow technique, or DCF. The key here is to figure out how much money you can take out of the business over the course of its whole life cycle and, more crucially, how much that money is now worth.

Across the analysts’ population, DCF method is widely used, and hence we have tried to look into this method in a bit detail here. Three primary variables are estimated in a DCF method –

- the terminal value (at the conclusion of the relevant investment period) or, alternatively, the terminal growth rate;

- the cost of equity/expected rate of return (the annual discounting rate applied to the cash flows); and

- the annual cash flows over the relevant time period.

Make sure to note that you will need to estimate a large number of sub-variables in order to get at these three big variables. For instance, in order to determine the yearly profits or cash flows, you must measure the revenue as well as the expenses and margins. The valuation you reach at using a DCF model will alter if you modify even one variable. A DCF model will also provide a different value if the same adjustments are made to the assumptions but in different years. Fair value in this method is therefore determined by a number of elements.

Next valuation method is Relative Valuation.

Relative valuation is a valuation approach that allows investors to assess a company’s worth by comparing it to similar firms.

According to studies, relative valuation accounts for around 85% of equities research analysts’ valuations and 50% of corporate M&A transactions. So, what precisely represents the relative valuation? It is the practice of estimating a stock’s fair value based on how it is valued in relation to a variety of elements. So, whether a stock’s PE is 15, 25, or 35, the only method to determine if it is cheap or expensive is to compare this single figure to its prospects for growth, competitor business multiples, sector pricing range, historical mean PE, current interest rates, and so on.

Stock market professionals and many prominent fund managers across the world feel that quantitative valuation (such as the DCF technique) is the superior way to determine the worth of a stock. However, due to the challenges involved in developing suitable models, inadequate data, time limitations, and the fact that there are several hundred stocks to consider, it is simply not possible to conduct a DCF (discounted cash flow model) for all of your equity investments, and thus relative valuation as a method of selecting stocks is commonly employed and accepted in the investing marketplace. When you purchase or sell a stock based on its PE, P/B, EV/EBITDA, or any other multiple, you are engaged in relative valuation.

In relative valuation, the more broadly you examine the value of the asset, that is, when you compare the valuation multiple to more characteristics, the better your viewpoint. Given that relative valuation is dependent on comparisons to peer multiples, investors must take steps to ensure that the reference multiples are appropriate as well.

Final words

The fundamental principle underlying the ‘valuation’ is to assess or estimate the worth of a company or business, and to figure out whether it is undervalued or overpriced. When choosing a stock valuation method, it’s simple to get overwhelmed by the variety of approaches accessible to investors. Certain techniques of appraisal are rather simple. Others are more intricate and detailed. Every business or sector has distinct features, and every stock is unique. As a result, a company’s value can be determined in a variety of ways, and no single figure or method can precisely capture its true worth.